Fly Rod & Reel: Who Hates Trout Rivers?

Reprinted with permission.

By Ted Williams

Who Hates Trout Rivers?

West Virginia is soiling some of the East’s finest wild-trout water.

As the bumper sticker proclaims, “Sh*t happens.” But it shouldn’t happen on blue-ribbon trout streams; and when it does, it means that government regulatory agencies are malfeasant, citizens disengaged and values warped.

Which takes us to West Virginia, where it has long been acceptable to extinguish aquatic ecosystems with acid-mine waste, blow up mountains and bury streams and valleys with “overburden”—in other words, everything living and dead that isn’t coal. Now, apparently, it’s OK to run raw sewage in plastic pipes along, around, over and under what is generally considered the best wild-trout water in the state.

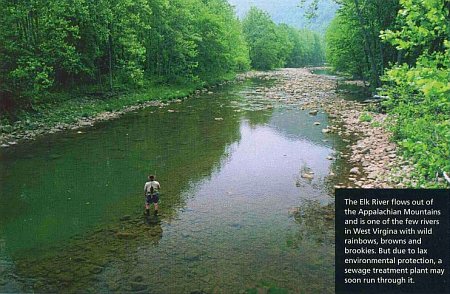

This latest insult is planned for the upper Elk River [here and here], one of the very few West Virginia streams (maybe the only West Virginia stream) in which browns, rainbows and brookies spawn. It also sustains the planet’s entire population of imperiled Elk River crayfish, listed as “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources on its Red List, the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the global status of plants and animals.

The major limiting factor for wild trout in West Virginia is the state’s relatively warm climate. But that’s less of a problem on the Upper Elk because a major tributary, Big Spring Fork, dips in and out of at least 68 karst caves and springs, charging the Elk with icy, oxygen- and limestone-rich water in which browns and rainbows commonly grow to five pounds. In most summers, Big Spring Fork flows almost entirely underground.

PVC pipe will carry as much as 1.5 million gallons of raw sewage a day from the Snowshoe/Silver Creek Ski Resorts (under single ownership but commonly referred to as just “Snowshoe”) along Big Spring Fork’s steep, tortured eight-mile course to the community of Slatyfork.

The sewage line will terminate at the Sharp family farm (founded in the early 19th Century by William Sharp III), where a $20 million “regional” sewage treatment plant is to be built by the Pocahontas County Public Service District with mostly state and federal funds. The construction site is a karst floodplain in a wet meadow where springwater bubbles and sometimes gushes from the earth and where sinkholes (the most recent 40 feet wide and 30 feet deep) open periodically.

The plan, approved in 2006, calls for a pumping station close to or possibly over part of a cave called the “Root Canal” because it’s so near the surface of the earth that tree roots dangle from the ceiling. Treated effluent will be vented into the top of the Elk’s 4.5-mile catch-and-release stretch where the prolific trout population is sustained by natural reproduction.

The catch-and-release section near Slatyfork is big water by Eastern standards, a series of wide pools and gentle riffles where you can wade comfortably and lay out long casts. Hatches can approach blizzard conditions. There’s great streamer fishing in winter.

Dr. Charles Heartwell—a commercial fly tier for the past half-century and, until his retirement in 1996, the state’s hatchery supervisor—developed most of his famous patterns on the Elk after he’d conducted a three-year study of the aquatic insects of central West Virginia. I asked him how much raw sewage it would take to extirpate the Elk’s wild trout.

“You’d have to get a pencil and paper,” he replied. “You’d have to figure what you’re bringing in—the heat, the oxygen deficit—and you’d have to know how much the flow can stand. It probably wouldn’t take much. The stream is still one of my favorites, and the fishery has held up very well. But the system is way over-silted from all the development at Snowshoe; and there are flow problems from all the physical damage to the watershed up there and the timbering [of the ski trails on Cheat Mountain]. A sewage plant in this watershed is kind of like a nuclear-power plant; it would only take one leak. Can you safeguard against that one catastrophe? I doubt it.”

Heartwell’s analogy takes us most of the way; but it’s not entirely apt unless we’re talking about a mid-20th Century Soviet Union nuclear-power plant. While major leaks and overflows are not a routine part of nuclear-power production, the same cannot be said of the sewage-treatment business. Even at the most modern facilities built on solid, dry ground it’s not a question of if, but when.

Another avid Elk River angler is chemical engineer George Phillips, president of Eight Rivers Safe Development, Inc.—the citizen’s group working full time to save the upper Elk. Eight Rivers has taken the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to court for its slovenly and unlawful environmental assessment (EA) of the treatment plant and attendant “finding of no significant impact” (FONSI).

The 23-page document contains 11 brief sentences (but no relevant information) on karst, caves and springs. The single correct statement in those 11 sentences is that investigators failed to find “voids [caves] under any proposed structures.” This is because they didn’t look.

“A sewage spill in karst caves isn’t like a surface spill,” observes Phillips. “In a surface stream, you have impermeable rock as well as sunlight to break down organics. You’re going to kill fish, but the stream will eventually recover. It’s different with an underground spill. There are reaches of the caves that don’t always get water. Sewage would fester in there for years, continually contaminating the stream. We think DEP glossed over this in their environmental assessment and that it didn’t understand the geology and hydrology of the area.”

A study by Evan Hansen, president of the respected environmental consulting firm Downstream Strategies, found the following violations by DEP of the National Environmental Policy Act, which was adopted as state law by the West Virginia legislature: “1. A premature decision was made to issue this FONSI, even before the EA was completed; 2. The EA is flawed because it does not conform to state rules and federal regulations; 3. According to the regulations, DEP cannot issue a FONSI and must prepare an environmental impact statement; 4. No public meeting was held when alternatives had been developed, but before an alternative had been selected, to discuss all alternatives.... 5. No public hearing was held prior to formal adoption of a facilities plan.”

Matching DEP’s ineptitude and deference to the appetites of industry was the Army Corps of Engineers, which wrongly decreed that the proposed construction site—pocked as it is with sinkholes, springs, and “boil holes” (where water boils up out of the ground)—wasn’t in Big Spring Fork’s floodplain. It made this determination indoors, by looking at a topo map.

Why should state and federal taxpayers build Snowshoe a treatment plant? How can the state and county, with straight faces, call this a “regional” plant when something like 90 percent of the human waste will issue from Snowshoe, a private, commercial development?

Dr. Heartwell offers this: “The state doesn’t have to put it on the Sharp farm; it could put it on state holdings. I don’t blame Snowshoe. The state has offered this to them. The state has built them roads. I think the state has done enough for Snowshoe. The state’s embarrassing; and I worked for the state... Snowshoe is a multi-million-dollar operation. It has lots and lots of money; the state doesn’t have to build them this sewage plant.”

“Lots and lots of money” is an understatement. The resort’s Vancouver-based owner, Intrawest (purchased in 2006 by the even richer private equity firm Fortress Investment Group), owns a dozen other major ski resorts in Canada and the United States, including Whistler (British Columbia), Stratton (Vermont), Tremblant (Quebec), and Winter Park (Colorado).

Because crowding at ski resorts is a turnoff, Intrawest won’t say how many people visit Snowshoe each year, but it’s one of the 25 busiest ski operations in the US. With massive fake-snow production, skiing usually starts around Thanksgiving and runs through the end of April. Fourteen lifts provide a 2,300-person-per-hour capacity. There are 60 trails, eight bars, 16 restaurants, 11 shopping centers, a golf course and 1,800 housing units (including 1,400 rentals). The development covers only four percent of the taxable landmass in Pocahontas County, but Snowshoe pays more than 50 percent of the property taxes. The resort annually contributes about $8.5 million to the state’s economy, a figure that has doubled in the past decade.

Its economic contribution notwithstanding, Snowshoe hasn’t been a great neighbor. In order to make fake snow, irrigate lawns and provide water to its residents and businesses, it has dammed and dewatered the Shavers Fork, once a fine trout stream in its own right and a rich source of cold, clean water for the acid- and heat-stressed Cheat River.

For repeated permit violations at its three existing sewage treatment plants, Snowshoe was recently fined $2.9 million. Of this DEP forgave $2.7 million because Snowshoe promised to turn over those three dangerously dilapidated plants—along with all past, present and future liability—to the Pocahontas County Public Service District. That, of course, is precisely what Intrawest was hoping for.

One might suppose that the main source of public outrage here would be the imminent threat to human health, the environment and wild trout. But no, it is property rights. And for once property-rights groups have something legitimate to bitch about in the impending seizure by eminent domain of the Sharp family farm. Unfortunately, however, they can’t offer the family much more than moral support because most of their charters and by-laws forbid legal involvement where condemnation is officially (if not actually) for the public by the public.

That’s not to say that the environmental community, anglers, and spelunkers haven’t responded. But, in West Virginia, they don’t have a lot of political clout.

And, with the exception of the spelunkers and the members of Eight Rivers Safe Development, they could certainly be making a better and more aggressive effort. Outdoor writer and fish activist Beau Beasley—who has done more than anyone to focus the angling community on this impending tragedy—laments what he sees as torpor among his fellow trout fishers.

“You want to know who’s leading the charge to protect this river—cavers,” he says. “Fly fishermen are a distant fifth. After months of investigating the issues surrounding the Elk River I have discovered two things: First, DEP seems much more interested in protecting West Virginia business than the environment. Second, when it comes to protecting the state’s fragile watersheds, Trout Unlimited, at least on a state level, seems to have a very wait-and-see approach. If they wait much longer to act, there won’t be much left to see.”

In the fall of 2005, William Sharp III’s great-, great-, great-grandson, Tom Shipley, was dismayed to hear Snowshoe’s general manager read a letter of conditional support for the treatment plant from the West Virginia Council of Trout Unlimited. Shipley, who lives on the Sharp farm and owns and operates Sharp’s Country Store and Museum and Bed and Breakfast on Big Spring Fork, posted the facts about the project on a Web site called WVAngler.com. “That post got more hits than anything they’ve ever done,” he recalls. “The whole fishing community wrote letters, called the governor, blogged.”

To its credit, the council promptly withdrew its conditional support, at the same time expressing grave concerns about “the area’s geology and karst hydrology, the temperature of the proposed discharge, and sediment impacts” as well as “the effect of the proposed plant on the Upper Elk trout fishery, one of the best trout fisheries in the United States.”

More recently, it has chastened DEP as follows: “It is impossible to declare a finding of no significant impact without having first thoroughly evaluated all of the potential impacts. The lack of substantive environmental study leaves too many vital concerns unanswered for this project to move forward at this point.”

Finally, the council helped fund the study by Downstream Strategies. “We’re very grateful for that support,” says Shipley.

Shipley feels betrayed by the state and county. Eight generations of his family have lived and worked at the farm. Robert E. Lee slept in the log house. Shipley’s ancestors are buried in the wet meadow that will be seized and torn up by the county.

When Shipley gave up his antiques dealership in Indiana and moved here in December 2004 to run the family business, he wasn’t sure he’d done the right thing. But a month later he walked across the wet meadow, pronounced “dry” by the Corps, to the proposed site of the new treatment plant.

“The river takes a meander there,” he says. “Water was running under the ice. There were huge icicles hanging from the tree limbs, and the sun was shining at a low angle through everything. It was incredibly beautiful. I knew then I’d made the right decision.”

The prevailing wind will blow the bouquet from two enormous, open sewage vats onto and into his bed-and-breakfast and store, 1,000 feet away. Great for business.

Shipley tells me that, so far, his family has spent “several hundred-thousand dollars” on attorney’s fees. “We’re not wealthy,” he says. “But we have the resources to fight this and we will keep fighting because it’s wrong.”

Wrong and unnecessary. While Snowshoe desperately needs modern sewage treatment, its existing plants could be retrofitted with a technology called “immersed membrane,” a microfiltration system that removes even viruses and could at the very least double present capacity. It would cost no more than $8 million (compared with $20 million for the plant planned for the Sharp farm). Finally, Snowshoe could return clean water to the Shavers Fork, restoring the trout fishery it degraded and ending its current (and ecologically dangerous) inter-basin transfer of water from the Cheat River watershed to the Elk River watershed.

“Membrane systems are the recommended sewage treatment technology option for environmentally sensitive areas,” declares Phillips. “The upper Elk and Shavers Fork headwaters are world-class trout fisheries. In the Big Spring Fork there are reproducing rainbow, brown and brook trout and pristine caves and springs. If that does not qualify as an environmentally sensitive area, I don’t know what does.”

Dr. Heartwell has it right when he says: “We don’t have very good water laws in West Virginia; and industry can do pretty much what it wants.”

But federal law—namely the Clean Water Act—is plenty good when it’s enforced. The trouble is, West Virginia not only declines to enforce this statute; it habitually violates it. That’s why state industries get to ruin trout streams whenever they so desire.

In order to come into compliance with the Clean Water Act, the state implemented a “tier” system for its streams. Streams with self-sustained brook trout populations received the highest ranking—Tier 3. Within their watersheds industries had to control their operations sufficiently that they didn’t impair water quality. Industries could legally damage Tier 2 streams; and they could pollute the bejesus out of Tier 1 streams. It was a decent system that would have upheld federal law and ensured the survival of wild brook trout—a national treasure and one of the state’s most valuable assets.

But industries (particularly coal mining, logging, farming and real-estate development) didn’t like the expense and bother of having to clean up after themselves. So they prevailed on lawmakers to hatch a new ranking for wild-trout streams—Tier 2.5, by which DEP would tolerate some pollution (or with its typical lax enforcement, a whole lot).

Big Spring Fork had been a Tier 3 stream; now it was a 2.5. But industry wanted still more. In 2007 industry lobbyists shouted down a DEP proposal to designate 309 trout streams as Tier 2.5, despite the facts that the agency had unimpeachable scientific data for doing so and that federal law required it.

“The hearing was so contentious they had negotiating sessions and compromise meetings,” recalls Don Garvin, legislative coordinator for the West Virginia Environmental Council, long-time TU member and former president of Mountaineer Chapter. “I’d been advised by Joe Lovett [director of the Appalachian Center for the Economy and the Environment] to just get as many Tier 2.5 streams as I could politically. So we agreed to a 156-stream compromise. But the timber boys and the Farm Bureau wouldn’t give in. And they were threatening to scuttle the whole thing.”

Now Big Spring Fork is right where Snowshoe wants it—Tier 2. “It has been downgraded in order to facilitate future development,” says Phillips. “The approach we seem to take here in West Virginia is let’s keep a trout stream at 2.5 until someone says ‘I want to log or I want to mine coal or I want to develop.’ Then we lower it to 2. The reason for Tier 2.5 was to balance industry against resources. But whenever industry came in, a stream got lowered to 2. It all came to a head in June. I went to the public hearing and made some comments on Tier 2.5. There were hundreds of trout fishermen. It was the most heavily attended hearing DEP has ever had.” But, as always, industry got its way.

So, at this writing, all West Virginia streams (save one on private land nominated by the enlightened owners) are downgraded to Tier 2, the default category.

Such is environmental protection in West Virginia whenever industry demands to feed at the public trough. May the state’s magnificent wild trout persist until better days.

Ted's column appears in every issue of FR&R.