The Weight of Souls

For fall I needed to understand this part.

October 30, 2006 - All summer I'd meant to get here, but never did. It's just as well, because fall is what made today's sights possible. From atop this mountain, through the bare trees I see the Sharp's Country Store, Hugh's cabin, and the bed & breakfast down in the valley. And I can also see, to the left, the proposed field kept by the Old Guardian.

Atop this mountain, we meander respectfully through the Sharp Cemetery. I read the engravings upon their headstones as Tom shares with me memoried stories of his ancestors. Here in front of me is Hugh Sharp, the rifle-bearing man in that old picture. And here is his father, William III himself, the first to build a house in what is known today as Slatyfork; down where Laurel Run merges into the Elk River.

We sit for a breather upon two stone benches at the cemetery's corner. Earlier today on the other side of Route 219, Tom showed me the woods and meadows of the northern portion of Sharp land. There, nearly centered in a large high meadow is a small ailing shed which strains to stand, tended to by a few apple trees that keep watch over those parts.

As we sit by the cemetery, it becomes the quietest moment of the day. No sound from the 4-wheeler, nor from us. I look out upon the plots, over and between and through the headstones. Impossible as it surely is, I nevertheless attempt to imagine, to understand what their lives and hopes must have been.

"My Great Uncle Dave planted so many apple trees all over this property," Tom interjects the silence readily. It is clear he has sat here many times.

A couple of years back, Tom continues, he and Dave trekked all over the property as Dave showed him what sounded like each and every apple tree he planted. "He's 90 years old, and if you even look cross-eyed at an apple tree like 'Oh we oughta trim that limb—Oh, No!'" would be Dave's admonishing response.

My laughing breaks the weight of attendant souls.

"He knows all about where he got the graft from and when he did it..."

Contently, pleasantly, the headstone shadows grow longer.

We leave the Sharp Cemetery, get on the 4-wheeler, and start heading down to the stream of Slaty Fork; the old homestead of Silas Sharp, and the site of the first store built by Silas' son L.D. (who in turn is Dave's father).

"Will we see any of Dave's apple trees at the old homestead?" I ask with tourist-crazed, camera-happy enthusiasm.

"I'm sure we will."

"You say you and Dave were 4-wheeling up here a couple years ago; how'd he do?" I figure he must have been about 88 after all, and my young body was already beat.

"He did fine. But that was the last time he'll make it up here," Tom despondently replied.

Half way down this pristine section of the abandoned Huttonsville-Huntersville Turnpike, I start to sense where we are based on the old photo of the homestead. Above and to our left runs Slaty Ridge, populated with trees, some still small enough to evoke the memory of the barren hillside from the photograph. And below and to our right runs Slaty Fork, but I can't see it yet.

Presently the grade levels off, and in front of us the road curves right over Slaty Fork, over the old bridge.

The Slaty Fork Bridge is a most grand and durable testament to the ebb and flow of generations. Its arched form is graceful and strong, still. Its walls dignify the history and soul of this time-wandering highway, and its surface records the memories of the countless feet that trod here, the heritage weaved through the innumerable patrons of the first Sharp store.

Standing upon this bridge, looking back the way we came I spy a structure through the leafless inquisitive trees. It is the home that Silas Sharp—the Civil War POW who walked back to Slatyfork from North Carolina—built here in the late 1800s. It is difficult to reconcile with the image of the old photograph. But there, readily visible, is the chimney, and it suffices in this task.

Those lives and hopes they seek to understand.

"It's a shame," Tom professes. I hear him, but not really.

Undeniably though, Silas' house is in ruins. The impressive chimney, the patriarch of shaped stones still stands, embraced by the dead grasp of its companion wall. A portion of the wood-shingled roof begs skyward, asking why. Disoriented confused boards huddle together in small directioned groups, each cluster purposefully, dutifully, but futilely looking for a solution.

"I remember as a boy, being inside when the roof was still fine," Tom reflects. I begin to hear him more properly now.

"It's still beautiful," I offer, not at all emptily.

Off to the right, not in the photograph, there is an old cellar house, twisted but standing. The doorway into the lower concrete portion reveals bins. "That's where they kept potatoes."

Around its right wall, foundation bulging, small trees are growing right up its side as if to do all they can to support it. Around back, the doorway to the upper floor reveals some kinds of wooden furniture; abandoned as with the highway. The cellar leans towards Silas' house, which is some two hundred feet or so to its left. Desperately, its gaze reaches out and over the stone sheep fences to the patriarch. You can hear the chimney. "Hang on, hold on, I'm coming."

Yes Tom, it is a shame.

There is little evidence of L.D.'s house. It was attached to Silas' home at the chimney wall. One can plainly see the doorway in that wall which allowed passage between the two homes.

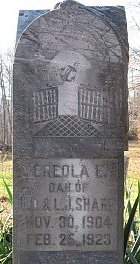

Nearly impossible to detect is the presence of the first store building. But the boundary of the larger, encompassing store addition is plainly visible. Some sort of kettle, broken-sided, sits unattended upon a substantial piece of the addition's foundation. And without too much imagination, one can picture where Creola was standing in the old photograph; she is the littler of the girls standing in the doorway of the store with her sister (Ada or Violet).

Moving back from the old homestead, I seek out the vantage point of that old photograph. As I search for this spot, more and more trees come between us. Now I am across the road, standing in about that same spot. There are so many trees, I can't see a thing of old.

"There's one of his apple trees, right there!" Tom proclaims excitedly, as if now a tourist himself. Just to my left, back across the road, a straggly old fruit-bearing apple tree smiles insistently. I encounter its gaze cautiously and respectful-eyed, and convey without contest that its limbs are fine by me.

Contently, pleasantly, the tree shadows grow longer.

We stroll downstream a bit and look upon a splendid waterfall about 50 yards from the bridge. The water flows free and clear, and I finally understand with equal clarity Tom's words in full.

His message is that we are not looking just at the past, at the ancestry of Sharps and Slatyfork, but also into a possible future. Into a time when once again the fruitful enterprise of generations will be left to the decay of time, when once again the priceless heritage of a community will be abandoned by something claiming to be progress, when once again the present blood of generations will be forced to adapt, to regroup their land, their lives and their hopes.

His message—which is that of many people—is that this future doesn't have to happen again.

his family's heritage in Pocahontas County, West Virginia.

While sitting at the Sharp Cemetery earlier and listening to Tom's telling of Dave's apple trees, I thought for a moment of the arrows upon Dave's and his wife Sylvia's headstone. Her arrow points up to Heaven as of 2004. But his arrow—in typical Dave humor Tom assured—presently has a question mark in the middle and points both up and down!

Inevitably, there will be a day when Dave Sharp does make it up here one last time. And when he does, his soul will add to The Weight of Souls which, centered upon all the Sharp land, will continue to admonish a ripe red "Oh, No!" to those who would unjustly seek to trim the branches of heritage.

Dave's double arrow, I think, is a most perceptive characterization of the uncertainty now inherent in the future of Slatyfork—and indeed of Pocahontas County, West Virginia. Clearly, Dave Sharp is far more than just funny.

From them we grow.

From fathers and mothers,

Our grafts we know.

Thus wisdom, through succession

Of blood is granted

To those who know best

How the future be planted.

Copyright © 2006 by David March Fleming

Old homestead photo used with permission.